A space forms after a big project; small ones, too, actually. I’ve had this feeling after finishing short pieces, like a story or an essay, and it happens especially after finishing a book. And it happens in stages, because finishing happens in stages—you complete a round of edits and there it is: a space forming, or a pause that’s both bright and shadowy. The world had been full of words and then suddenly it isn’t. Or the words have changed, maybe, neglected ones coming to the surface, or maybe it’s images or sensations. Something, anyway, is different.

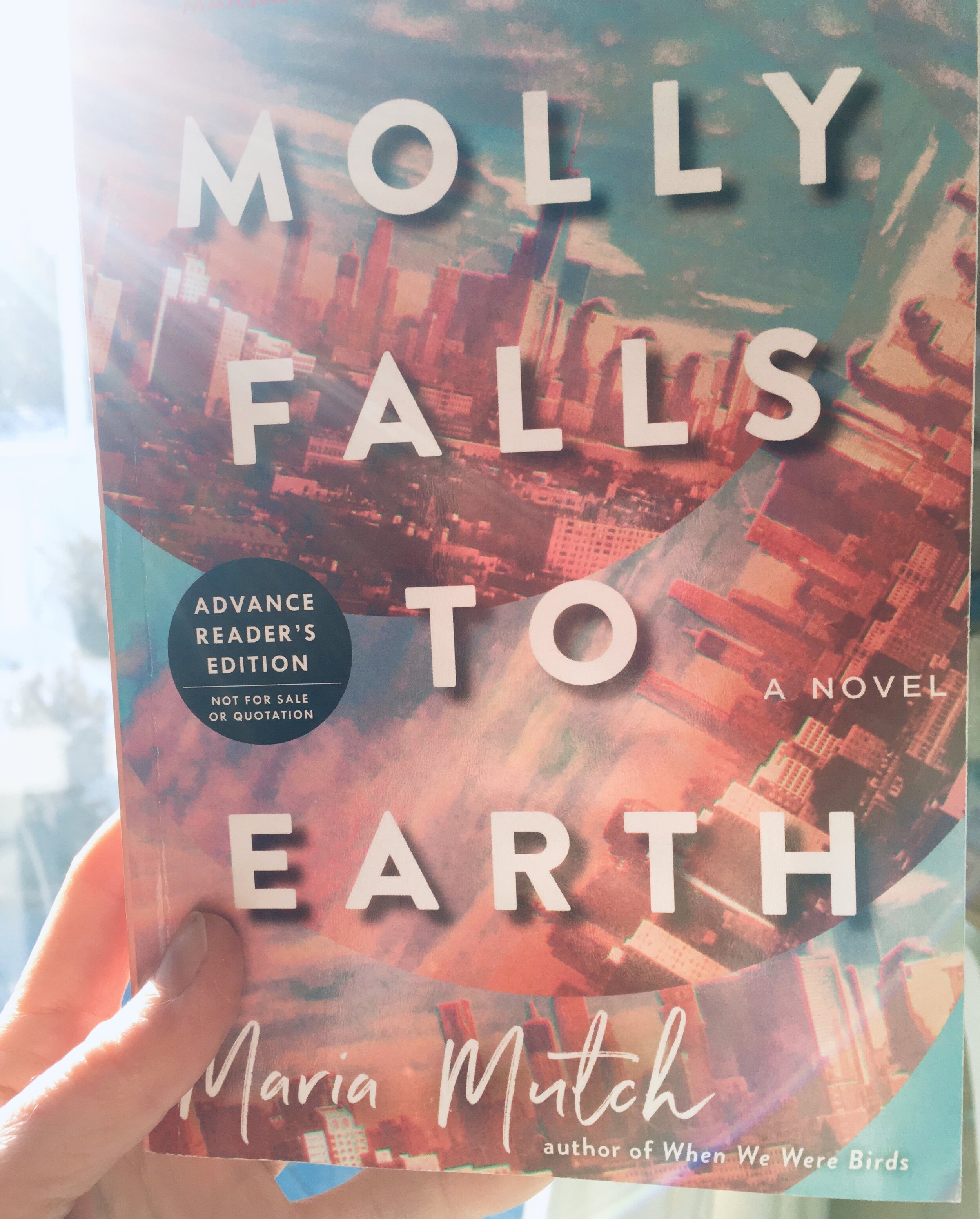

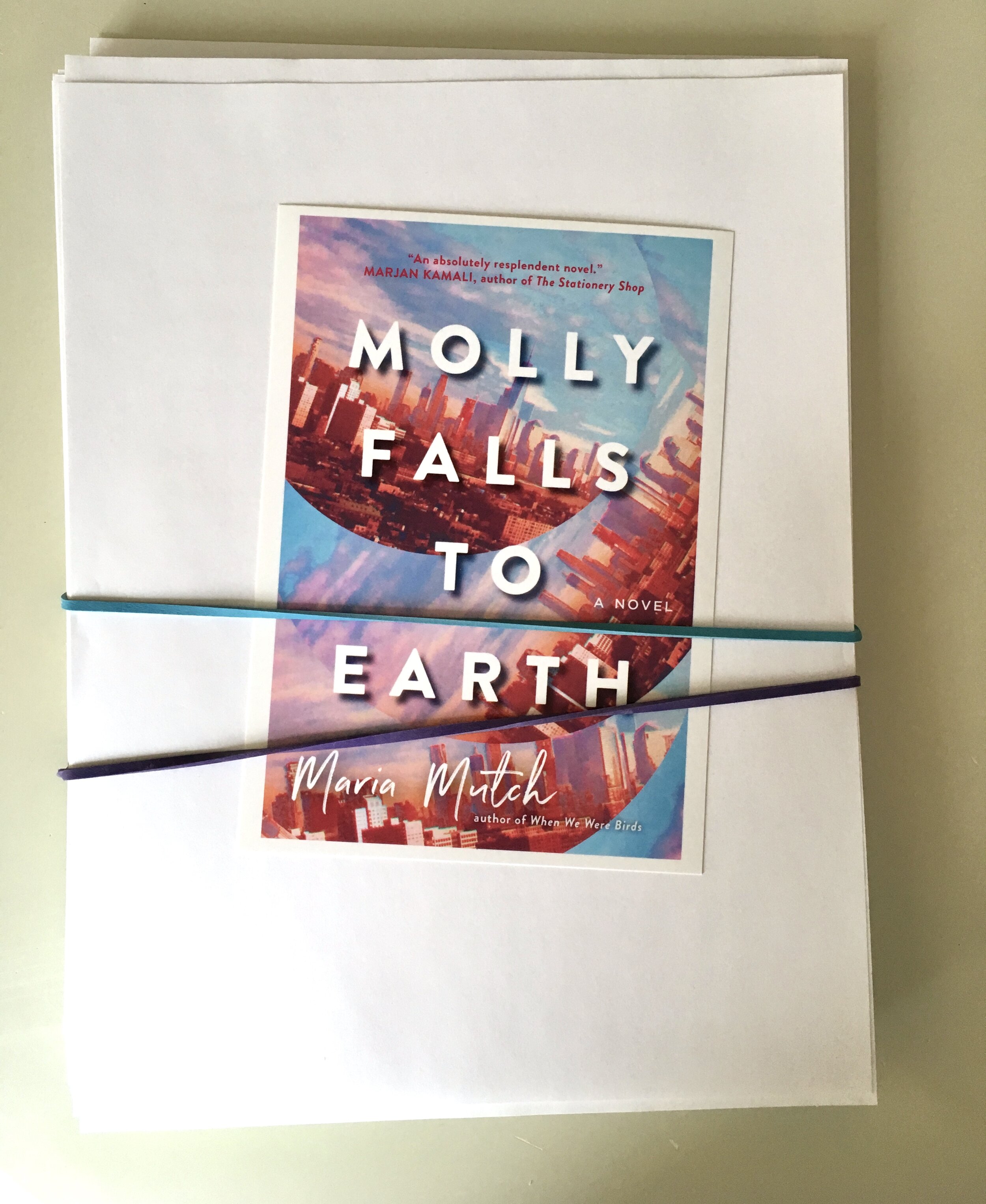

Some writers have the next book already queued up, so one project is simply exchanged for another in a seamless word fabric. When I finished my story collection, I was in that position, having already started MOLLY FALLS TO EARTH because it began, literally, as one of the stories before I understood it wanted to be something bigger and removed it. But I still took a pause, or rather the pause took me, and there was that space again, both welcome and uncomfortable. If you’re too hooked on doing, the space can be disconcerting. Somehow boundaries have shifted, gotten bigger and maybe unwieldy. New terrain, or old terrain that had gone unseen for a time. But I know better than to avoid spaces and pauses; they’re maybe the most important “thing,” for not being a thing.

Anyway, the photos above. They’re of Washington Square Park. Molly, my novel’s protagonist, is a contemporary dance choreographer who has a seizure on a sidewalk in Manhattan—right on the edge of WSP. Her seizure lasts seven minutes, which is the crux of the book, as she experiences a confluence of her past and her present, including her secrets, and the people who have gathered around her. WSP is the kind of smallish park that seems big in memory. It has an outsized history and presence and colour. The trees and plantings in it are wondrous. The people, too. The wanderers and settlers and chess hustlers. There’s an enormous English elm that’s perhaps 300 years old, and there are some 20,000 people buried beneath the park’s surface. Walkways weave through that are made of hexagonal pavers. There’s the fountain, of course, and the gleaming white arch, and the beginning of Fifth Avenue. It’s been the scene of untold protests and subversive gatherings, and you can feel that energy when you’re there, all the possibilities.

So, the photos. I took some of them in summer and some in winter. Naturally, the park changes dramatically and when the branches are bare and you can see the curving shapes of them against the sky, there’s a spookiness and atmosphere. Not unfriendly in the least, but certainly stopping. The photos I took are mostly very simple, and quiet, and I avoided shooting people or the arch or the fountain. I took numerous shots of the hexagons, and some of the chess pieces, and a couple of pigeons; also various bits of litter: an old crossword, a folded blue-lined paper, a crumpled napkin. A small delicate white feather. When I shot there in summer, I was with my husband, and the park was full of movement and people. I was busy, focused on my camera, with my gaze mostly to the ground, looking for interesting items. I missed, according to my husband, the bare-chested woman sunning herself on a bench very close to me. And no one paying much mind, this being New York.

Back to space. I realized the photos are a kind of space or pause. The mind can’t help making its interpretations, it has to come up with a story or a meaning of some kind when it sees a picture—it’s almost helpless to the process, I think—but at the same time the image in amongst prose forms a void, or it can. And that’s one of the reasons that I find images within novels and short stories so fetching. There’s a shift, even one that’s in a blink, and something opens up that feels, if you’re open to it, almost eternal. Or something like that.